Seaside Liberation

Kat Morris

3/3/20237 min read

It's Kat and I wanna chat about environmental justice. No surprise there, but what might surprise you is the story I’m about to share. That is the super dope history of Black and Indigenous liberation harbored in our very own Bridgeport, Connecticut (CT). Did you know that in 1969, the first Black Panther Party chapter in CT was organized in Bridgeport? Soon after, New Haven became the state’s Panther Headquarters and home of the John Huggins Free Breakfast for Children Program. Did you know that in 1915, 1,000 women corset workers began to strike demanding the eight-hour day, removal of unjust rules, and union recognition at Bridgeport’s Warner Corset Company? Roughly 14,000 factory workers all around the city seized the opportunity for a general strike as Bridgeport was dubbed “The Essen of America,” during the war-boom producing two-thirds of all small arms and ammunition being shipped from the United States to the Allies (Bucki, 2001). Not only did the Bridgeport strikers become a national spotlight, setting the stage for labor activism the following year, they won the eight-hour-day. The Bridgeport strikers won.

Dear ConnectiCunts,

To learn more about Kat Morris and support Seaside Sounds for Environmental Justice, check out IG: @morhkat, Twitter: @kattatatt, or katmorris.me <3

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” – Marcus Garvey

A Path to Freedom

This story of liberation begins with its antithesis, slavery. Who woulda thought? Contrary to popular belief, climate change and environmental racism are inseparable from slavery for three reasons. First, the utter disregard of life (human and environmental) for capital gain. Second, slavery facilitated the industrial revolution through the consistent exploitation of natural resources without regard for the ecosystem. Third, the genocide of Indigenous populations, which preceeded and coincided with slavery, devastated native culture, including knowledge on land stewardship. I offer these three reasons to challenge the idea that achieving climate sustainability and environmental justice are two separate objectives. They are one in the same. I offer this story with the understanding that there will be no climate justice without remedying environmental racism, and that requires rediscovering the history of systemic racism in America.

By the American Revolution, CT had more enslaved Africans than any other New England state (nps, 2017). In 1784, the state passed an act of ‘Gradual Abolition’ dictating that children born into chattel slavery after March 1, 1784 could be freed in March 1809, after enduring 25 years of ‘servitude’ (i.e slavery) alongside their mothers. This act did not free anyone in real time, nor did this conditional eligibility extend to the children’s parents or older siblings (Menschel, 2001). Ultimately, slavery was officially practiced in CT until 1848, making it the last New England state to fully abolish slavery (nps, 2017). (#embarrassing) As we’ve been taught, slavery was “abolished” via the 13th Amendment in 1865. (Watch the documentary, 13th on Netflix to learn how the 13th amendment legally transformed slavery into modern mass incarceration.) Before this amendment, however, the U.S government passed the ‘Fugitive Slave Act’ statutes in 1793 and 1850, which sactioned the capture and return to slavery of those escaping enslavement, typically via the Underground Railroad.

Quick question: how old were you when you realized that the Underground Railroad was neither underground nor a railroad? As a child, I remember being very curious and wishing to one day explore this liberatory infrastructure. Now I understand that this path to freedom entailed enslaved people from the South following the North Star to find a sophisticated system of safe havens and multi-modal transit. Although some details were lost in the secrecy, CT has identified many of its Underground Railroad sites on the Freedom Trail. This trail spans the state with various routes through Stamford, New Haven, Hartford, Bloomfield, Putnam, New London, Farmington, and many more (CT Historical Commission). I want to focus on the Underground Railroad site where my childhood wish came true, the South End of Bridgeport.

"In Bridgeport the blacks may reign. This, then, is the spot for respectable colored people. Let them never play the tail part anywhere, when they can play the head.” – Correspondent, Ethiop – Frederick Douglass’ Paper, September 1, 1854

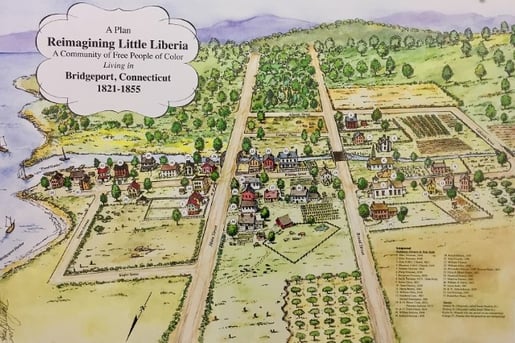

Little Liberia

The South End of Bridgeport was once known as Ethiope before being dubbed Little Liberia circa 1821. Liberia means ‘land of freedom’– aptly named, not only was Little Liberia an Underground Railroad destination, but also a prosperous seafaring community of free African and Native Americans (e.g Paugussett tribe) who lived off the land and advocated for human rights, inviting like-minded people of color to join them. According to Shinnecock oral tradition, the Long Island Sound provided food for the ‘garden community’ and night time canoe crossings on the Underground Railroad. Little Liberia held Bridgeport’s first free lending library, a school for colored children, businesses, fraternal organizations, and churches, as well as a renowned seaside resort hotel for wealthy Black patrons, as well as the stunning Seaside Park. Their seamen whaled, sailed Caribbean packet vessels, harvested oysters, and allegedly fought pirates! When they returned to Bridgeport Harbor, these seamen brought their earnings home where many women owned and/or maintained family businesses and property.

Women of Little Liberia, like Mary Freeman (1815–1883) and Eliza Freeman (1805-1862) were well accomplished in business long before the U.S government gave us the right to vote. Born in Derby, Connecticut; Eliza and Mary Freeman were sisters of mixed ancestry (African American & Paugussett) who purchased adjoining lots on Main Street in Little Liberia. They finished constructing their houses in 1848, the same year Connecticut finally ended slavery, and hustled for decades, developing and selling real estate while working other jobs. When Mary Freeman died, her wealth rivaled that of legendary showman P.T. Barnum. Of the estimated 36 structures that comprised Little Liberia, only the Freeman Houses survive on original foundations. For this, they are listed on the National Register of Historic Places for their significance to African Americans and Women, and preserved today by the Freeman Center. They stand today as a tangible reminder of this great community’s legacy of liberation.

Little Liberia turned 200 on April 10, 2021 Happy 201st!

In telling this story, I must share that of the illustrious Maisa Tisdale. She is the founding president and CEO of the Mary & Eliza Freeman Center. Born and raised in Bridgeport, her roots to the land run deep as six generations of her family were born in and/or have lived in Bridgeport. Maisa’s work teaches us how past prosperity produces present day progress… but not without proper preservation and public perception. In 2009, she successfully advocated for the preservation of the Mary and Eliza Freeman Houses, saving them from demolition, later founding the Mary & Eliza Freeman Center for History and Community (Freeman Center, 2022). Today, she advocates for historic preservation and community development in Bridgeport's South End through the Freeman Center, as well as environmental justice and climate resilience via Resilient Bridgeport. Check out ‘Resilient Bridgeport’ to learn about the climate resilience strategy prototyped to protect the South End neighborhood, a FEMA flood zone, from chronic and acute flooding in order to foster long-term prosperity (Resilient Bridgeport, 2022). In other words, Maisa Tisdale is a brilliant and accomplished Black woman who leads with integrity, ushering the wisdom of the past into the present.

"It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains" – Assata Shakur.

Liberating Seaside

I tell the story of Little Liberia not simply to share its dope history, but to make a connection. Before going to UConn, creating UCCO, and becoming the scholar-activist y’all know today, I lived in Bridgeport’s West End and attended Bassick High School and BRASTEC (aka Aqua). I ran track and field (#400m), played volleyball, and often volunteered with buildOn. One volunteer project we did was a beach clean-up at Seaside Park and Beach. Seaside quickly became my own safe-haven for me as nothing brings me more peace than being surrounded by bountiful trees and water-bodies. This gorgeous and criminally underrated park is great for a pleasant bike ride, picnic date or family cookout, volleyball tournament, an L walk, or simply listening to the waves crash as you watch the sunset over the Long Island Sound, Seaside is perfect! Or it was…It can be.

Today, it is no longer recommended that the community harvest oysters for a free meal as they once did. While some still will, all the stormwater and sewage pollution in the Sound makes that a bad idea. Tormenting my moments of blissful peace is the sight of the PSEG gas plant sitting at my favorite end of the park, and the state’s largest incinerator, the Wheelabrator, sited near the beach end. In a previous piece for CTCunt, “What Spooks Me About CT”, I detailed health inequities associated with environmental racism. Let me be clear, locating a power plant (which used to be a coal plant, booo) and the state’s largest incinerator, and air and water pollution all in a predominantly Black and Latinx community, is environmental racism. Doing it in Little Liberia–disrespecting the legacy of Black and Indigneous liberation–simply adds insult to injury. What could make this worse? The City and State’s intentions to build a new Bassick High beside the gas plant, without conducting an environmental impact evaluation, or giving proper public notice! While one might think it cute to have the school near the park, this area is, in fact, a FEMA designated ‘Special Flood Zone Area’ due to the complete lack of climate resilient infrastructure along the Long Island Sound. Should this construction take place, students and staff will be at increased risk for respiratory illness while the greater impact to the natural and built environment will be unknown. Should this construction take place, it would be yet another example of careless decisions made today harming those of our community and the ecosystem, for generations to come.

I tell the story of Little Liberia because I believe that when we know what was, we can reimagine our future. Seaside Park sits in the heart of Little Liberia, making it a beacon of hope for environmental justice, despite its current afflictions. This is why I’m organizing Seaside Sounds for Environmental Justice. To share this history is to share the beautiful cultural significance of Bridgeport in the historic arc towards Liberation. To share this history is to share the truth of what our community faces today, but also what it has to offer. I believe this is paramount to moving us toward a brighter, more just future but more importantly, I believe in our ability to make environmental justice a reality.

I believe in our capacity to win. I can only hope you do too.

In loving solidarity,

Kat